Treatment for congenital heart disease depends on the specific defect you or your child has.

The majority of congenital heart disease problems are mild heart defects and don't usually need to be treated, although it's likely that you'll have regular check-ups to monitor your health in an outpatient setting throughout life.

More severe heart defects usually require surgery or catheter intervention (where a thin hollow tube is inserted into the heart via an artery) and long-term monitoring of the heart throughout adult life by a congenital heart disease specialist.

In some cases, medications may be used to relieve symptoms or stabilise the condition before and/or after surgery or intervention.

These may include diuretics (water tablets) to remove fluid from the body and make breathing easier, and other medication, such as digoxin to slow down the heartbeat and increase the strength of the heart's pumping function.

See types of congenital heart disease for descriptions of the different defects below.

Aortic valve stenosis

The urgency for treatment depends on how narrow the valve is. Treatment may be needed immediately, or it could be delayed until the development of symptoms.

If treatment is required, a procedure called a balloon valvuloplasty is often the recommended treatment option in children and younger people.

During the procedure, a small tube (catheter) is passed through the blood vessels to the site of the narrowed valve. A balloon attached to the catheter is inflated, which helps to stretch or widen the valve and relieve any blockage in blood flow.

If balloon valvuloplasty is ineffective or unsuitable, it's usually necessary to remove and replace the valve using open heart surgery. This is where the surgeon makes a cut in the chest to access the heart.

There are several options for replacing aortic valves, including valves made from animal or human tissue, or your own pulmonary valve. If the pulmonary valve is used, it will be replaced at the same time with a donor pulmonary valve. This type of specialised surgery is known as the Ross procedure. In older children or adults, it's more likely that metal valves will be used.

Some people also develop a leak of the aortic valve which will require monitoring. If the leak starts to cause problems with the heart, the aortic valve will need to be replaced.

Coarctation of the aorta

If your child has the more serious form of coarctation of the aorta that develops shortly after birth, surgery to restore the flow of blood through the aorta is usually recommended in the first few days of life.

Several surgical techniques can be used, including:

- removing the narrowed section of the aorta and reconnecting the 2 remaining ends

- inserting a catheter into the aorta and widening it with a balloon or metal tube (stent)

- removing sections of blood vessels from other parts of your child's body and using them to create an aorta in the region of the coarctation or bypass around the site of the blockage (this is similar to a coronary artery bypass graft, which is used to treat heart disease)

Sometimes, older children and adults can develop a newly diagnosed coarctation or partial recurrence of the previous blockage. The main goal of treatment will be to control high blood pressure using a combination of diet, exercise and medication. Some people will need to have the narrowed section of the aorta widened with a balloon and stent.

Read more about treating high blood pressure.

Ebstein's anomaly

In many cases, Ebstein's anomaly is mild and doesn't require treatment. However, some people may need medicines to help control their heart rate and rhythm. Surgery to repair the abnormal tricuspid valve is usually recommended if the valve is very leaky.

If valve repair surgery is ineffective or unsuitable, a replacement valve may be implanted. If Ebstein's anomaly occurs along with an atrial septal defect, the hole will be closed at the same time.

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

Some cases of PDA can be treated with medication shortly after birth.

There are 2 types of medication to effectively stimulate the closure of the duct responsible for PDA. These are indomethacin and a special form of ibuprofen.

If the PDA doesn't close with medication, the duct may be sealed with a coil or plug. These can be implanted using a catheter (keyhole surgery).

Sometimes the duct may need to be tied shut to close it. This is done using open heart surgery.

Pulmonary valve stenosis

Mild pulmonary valve stenosis doesn't require treatment, because it doesn't cause any symptoms or problems.

More severe cases of pulmonary valve stenosis usually require treatment, even if they cause few or no symptoms. This is because there's a high risk of heart failure in later life if it's not treated.

As with aortic valve stenosis, the main treatment for pulmonary valve stenosis is a balloon to the pulmonary valve (valvuloplasty). However, if this is ineffective or the valve isn't suitable for this treatment, surgery may be needed to open the valve (valvotomy) or replace the valve with an animal or human valve.

Some patients develop leaking of the pulmonary valve after treatment of pulmonary valve stenosis. This will require ongoing monitoring and if the leak starts to cause a problem with the heart then the valve will need to be replaced. This can be performed with open heart surgery or, increasingly, using catheter intervention which is a much less invasive procedure.

Septal defects

The treatment of ventricular and atrial septal defects depends on the size of the hole. No treatment will be required if your child has a small septal defect that doesn't cause any symptoms or stretch on the heart. These types of septal defects have an excellent outcome and don't pose a threat to your child's health.

If your child has a larger ventricular septal defect, surgery is usually recommended to close the hole.

A large atrial septal defect and some types of ventricular septal defect can be closed with a special device inserted with a catheter. If the defect is too big or not suitable for the device, surgery may be needed to close the hole.

Unlike open heart surgery, the catheter procedure doesn't cause any scarring and is associated with just a small bruise in the groin. Recovery is very quick. This procedure is undertaken in specialist units that treat congenital heart problems in children and a small number of additional adult centres.

Single ventricle defects

Tricuspid atresia and hypoplastic left heart syndrome are treated in much the same way.

Shortly after birth, your baby will be given an injection of medication called prostaglandin. This will encourage the mixing of oxygen-rich blood with oxygen-poor blood. The condition will then need to be treated using a 3-stage procedure.

The first stage is usually performed during the first few days of life. An artificial passage known as a shunt is created between the heart and lungs, so blood can get to the lungs. However, not all babies will need a shunt.

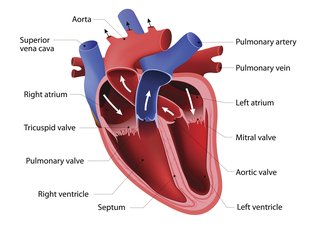

The second stage will be performed when your child is 3 to 6 months old. The surgeon will connect veins that carry oxygen-poor blood from the upper part of the body (superior vena cava) directly to your child's pulmonary artery. This will allow blood to flow into the lungs, where it can be filled with oxygen.

The final stage is usually performed when your child is 18 to 36 months old. It involves connecting the remaining lower body vein (inferior vena cava) to the pulmonary artery, effectively bypassing the heart.

Patients treated in this way with a single ventricle are complex and need lifelong specialist care. There may be significant complications after such complex surgery, which may limit the ability to exercise and shorten life expectancy. A heart transplant may be recommended for a small number of patients but is limited by the lack of available hearts for transplantation.

Read more about the heart transplant waiting list.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot is treated using surgery. If your baby is born with severe symptoms, surgery may be recommended soon after birth. If the symptoms are less severe, surgery will usually be carried out when your child is 4 to 6 months old.

During the operation, the surgeon will close the hole in the heart and open up the narrowing in the pulmonary valve.

Some patients develop leaking of the pulmonary valve after treatment of Tetralogy of Fallot. This will require ongoing monitoring and if the leak starts to cause a problem with the heart then the valve will need to be replaced. This can be performed with open heart surgery or, increasingly, using catheter intervention which is a much less invasive procedure.

Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC)

TAPVC is treated with surgery. During the procedure, the surgeon will reconnect the abnormally positioned veins into the correct position in the left atrium.

The timing of surgery will usually depend on whether your child's pulmonary vein (the vein connecting the lungs and heart) is also obstructed or narrowed.

If the pulmonary vein is obstructed, surgery will be performed shortly after birth. If the vein isn't obstructed, surgery can often be postponed until your child is a few weeks or months old.

Transposition of the great arteries

As with treatment for single ventricle defects, your baby will be given an injection of a medication called prostaglandin shortly after birth. This will prevent the passage between the aorta and pulmonary arteries (the ductus arteriosus) closing after birth.

Keeping the ductus arteriosus open means that oxygen-rich blood is able to mix with oxygen-poor blood, which should help relieve your baby's symptoms.

In some cases, it may also be necessary to use a catheter to create a temporary hole in the atrial septum (the wall separating the 2 upper chambers of the heart) to further encourage the mixing of blood.

Once your baby's health has stabilised, it's likely that surgery will be recommended. This should ideally be carried out during the first month of the baby's life. A surgical technique called arterial switch is used, which involves detaching the transposed arteries and reattaching them in the correct position.

Truncus arteriosus

Your baby may be given medicines to help stabilise their condition. Once your baby is in a stable condition, surgery will be used to treat truncus arteriosus. This is usually carried out within a few weeks of birth.

The abnormal blood vessel will be split to create 2 new blood vessels, and each one will be reconnected in the correct position.

Exercise

In the past, children with congenital heart disease were discouraged from exercising. However, exercise is now believed to improve health, boost self-esteem and help prevent problems developing in later life.

Even if your child can't do strenuous exercise, they can still benefit from a more limited programme of physical activity, such as walking or, in some cases, swimming.

Your child's heart specialist can give you more detailed advice about the right level of physical activity that's suitable for your child.

Page last reviewed: 12 June 2018

Next review due: 12 June 2021