Actinic keratoses, also known as solar keratoses, are rough patches of skin caused by damage from years of sun exposure.

They aren't usually a serious problem and can go away on their own, but it's important to get them checked as there's a chance they might turn into skin cancer at some point.

Symptoms of actinic keratoses

Actinic keratoses usually appear on skin that's exposed to the sun.

Common places to get them are the:

- face

- forearms

- hands

- scalp

- ears

- lower legs

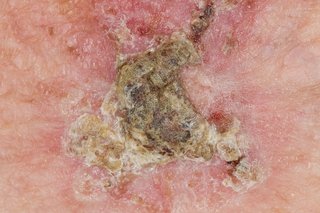

NAS Medical / Alamy Stock Photo

The patches can be:

- red, pink, brown or skin-coloured

- rough or scaly (like sandpaper)

- flat or stick out from the skin (similar to warts)

- a few millimetres to a few centimetres across

- sore or itchy

When to see your GP

See your GP if you have:

- an unusual growth on your skin that you're worried about

- a patch or lump on your skin that gets bigger quickly, starts to hurt or bleeds

- had actinic keratoses before and think you may have a new patch

It can be hard to tell if you have actinic keratoses. The patches can look similar to other conditions such as warts or skin cancer.

Your GP can usually check if it's actinic keratoses by looking at your skin. They can refer you to a skin specialist if they're not sure.

Treatments for actinic keratoses

Talk to your GP about the treatment options for actinic keratoses.

Sometimes they may just suggest that you check the patches regularly and come back if they start to grow quickly, hurt or bleed.

If the patches cause problems (for example, they're unsightly or sore) or your doctor is concerned they could turn into cancer, they may suggest treatments such as:

- prescription creams and gels – including 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream, diclofenac gel (this isn't the same as the painkilling gel you can buy) and ingenol mebutate gel

- freezing the patches (cryotherapy) – this makes the patches turn into blisters and fall off after a few weeks

- scraping away the patches (curettage) with a sharp spoon-like instrument called a curette while your skin is numbed with local anaesthetic

- photodynamic therapy (PDT) – where special cream is applied to the patches and a light is shone onto them to kill the unusual cells; this usually involves using a lamp, but sometimes natural sunlight is used instead

- cutting out the patches with a scalpel while your skin is numbed with local anaesthetic

The best treatment depends on how many patches you have, where they are and what they look like. Ask about the benefits and risks (such as side effects or scarring) of each option.

Looking after your skin if you have actinic keratoses

If you have actinic keratoses, it's very important to protect your skin from the sun.

This can reduce the risk of more patches appearing and may help reduce your risk of getting skin cancer.

To protect yourself from the sun:

- cover your skin with clothes and a hat during the summer months

- apply sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of at least 15 before going out into the sun

- try to stay inside or in the shade when the sun is at its strongest (between 11am and 3pm)

Read more sun safety tips.

It may also help to use moisturising creams (emollients) on your skin every day to stop it becoming dry.

Cancer risk and actinic keratoses

There's a small chance that actinic keratoses could eventually turn into a type of skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) if they're not treated.

You're at a higher risk if you have lots of patches for a long time.

Research suggests that people with several patches have around a 1 in 10 chance of getting skin cancer within 10 years of first developing actinic keratoses.

Signs that a patch has turned into cancer include it:

- growing quickly

- hurting

- bleeding

See your GP if you have these symptoms or if you get any new patches or lumps on your skin.

SCC can usually be treated successfully if it's caught at an early stage. Read more about treatments for skin cancer.

Page last reviewed: 8 May 2017

Next review due: 8 May 2020